Guide to Preparing Your Body and Mind for Deployment

Deployment (especially to a combat zone) is never easy, even in the best of circumstances. However, a rock-solid pre-deployment plan can make your next tour of duty significantly more bearable. Here we’ll cover the three most essential pillars of deployment readiness often overlooked: health markers, mental and cognitive development, and physical health and training.

Back to Basics: Three Things You Definitely Shouldn’t Skip

Many key aspects of soldiers’ health and well-being are often overlooked, by individuals and leadership alike. Focusing on these areas now can significantly boost your deployment readiness and overall quality of life if you maintain them consistently.

1. Regular, High-Quality Sleep

Chronic poor sleep is one of the single most damaging health conditions people can experience. It doesn’t just make you tired and grumpy; if it goes on long enough, it can cause high blood pressure, chronic headaches, heart disease, major cognitive decline, memory loss, sexual dysfunction, hormone dysregulation (including infertility in men), weight gain, depression, diabetes, stroke, and a whole host of other serious problems—including sudden death in some cases. For many people (especially military service members), chronic poor sleep is the root cause of several other significant mental and physical health problems.

Military life may not intentionally be hostile to good sleep, but in practice, it is hostile. Rarely (if ever) does military life naturally allow for consistent, high-quality sleep, but with some intentional strategy, you can at least mostly hit the target. Here are four of the best things you can try to improve your sleep before and during deployment:

- Make sleep time sacred: This is a major lifestyle adjustment for many military service members. However much time you have for sleep, it should be reserved for sleep, and nothing else should be allowed to interfere with that time other than lawful orders and major emergencies. To the greatest possible extent, make your sleep area private, quiet, dark, and cool. Ask others not to disturb your sleep for any reason short of lawful orders

- Frame your needs properly to your coworkers and superiors: Unfortunately, the military rarely makes soldiers’ health a high priority—unless you make the argument a certain way. You stand a better chance of getting others to allow you time and space for good sleep if you can successfully argue two points: (1) your mission readiness is currently suboptimal, and (2) it will improve markedly if you start getting better sleep.

- If all else fails, adapt: Even with a medical recommendation and persuasive argumentation, you may not get the framework you need for good sleep. In that case, sleep as much as you can, when you can (without defying orders or otherwise getting in trouble). Even a 30-minute catnap is markedly more restorative if you can do it in a dark, quiet place as opposed to sleeping in a corner of a bright, noisy room.

2. Active Stress Reduction and Management

Few careers are more stressful than military service, and stress peaks before and during deployment. Accumulated stress rarely resolves passively; management and reduction of stress usually requires conscious thought and effort. Like poor sleep, chronic stress has severely debilitating effects on both mind and body.

Like diet and exercise, stress-management techniques are highly individual; what works exceptionally well for someone else may not do much for you, or vice versa. With that in mind, here are our four best tips for minimizing the harmful impacts of stress:

- Write about it: You may roll your eyes at this advice, or you may be inclined to say “I’m not really a writer,” but engaging with your own thoughts in writing really is the closest thing there is to a panacea. Writing is and always has been the single best way to improve one’s thinking, and improving your thinking improves your ability to understand, mitigate, and correct the stressors in your life. You don’t have to share your writing with anyone, although you can; a private journal is an excellent starting point (as long as you’re always brutally honest with yourself).

- Talk about it: If there’s even one person in your life whom you trust and who is willing to reciprocate, talking about your stress regularly is very helpful as long as your discussions are ultimately solution-oriented; beware venting for its own sake, which often makes stress worse.

- Make R&R a high priority: “Me time” is critically important and, like good sleep, it’s often downplayed or ignored in the military. Spend time with friends and family (or by yourself), doing activities you enjoy, as much as your military work schedule allows.

- Make future goals and work towards them: During deployment, it’s often hard to think about much other than getting through it one day at a time. Even so, having a long-term goal that’s personally important to you, and working toward it consistently, is one of the best antidotes to stress, apathy, and depression. Try to get into the habit of thinking in terms of “after this deployment” or “after my enlistment term” (if you don’t plan on reenlisting). Deployment may feel like an eternity, but it is temporary.

3. Work on Your Relationships

If your personal and professional relationships aren’t rock solid, deployment gets even harder. Pre-deployment, your time and energy will be limited, but even so, it’s critically important to use whatever time you have to invest deeply in the people closest to you. This isn’t just about solving relationship problems or challenges, although that may be necessary. It’s ultimately about creating a consistent habit of doing something every day to improve your relationships, even if only slightly. During deployment, you’ll need as many close and trusting bonds with your fellow soldiers as you can get. Similarly, your non-military relationships will be powerful positive motivators if they’re in good shape, and they’ll be profoundly negative motivators if they’re rocky.

Mental and Cognitive Development

Military pre-deployment training generally focuses heavily on physical readiness, which is certainly important, but mental and cognitive readiness is the most important factor of all, and yet it rarely receives proportionate emphasis in training. Given that your time and energy are limited, here are three of the most high-leverage things you can do to keep your mind fresh, flexible, and active.

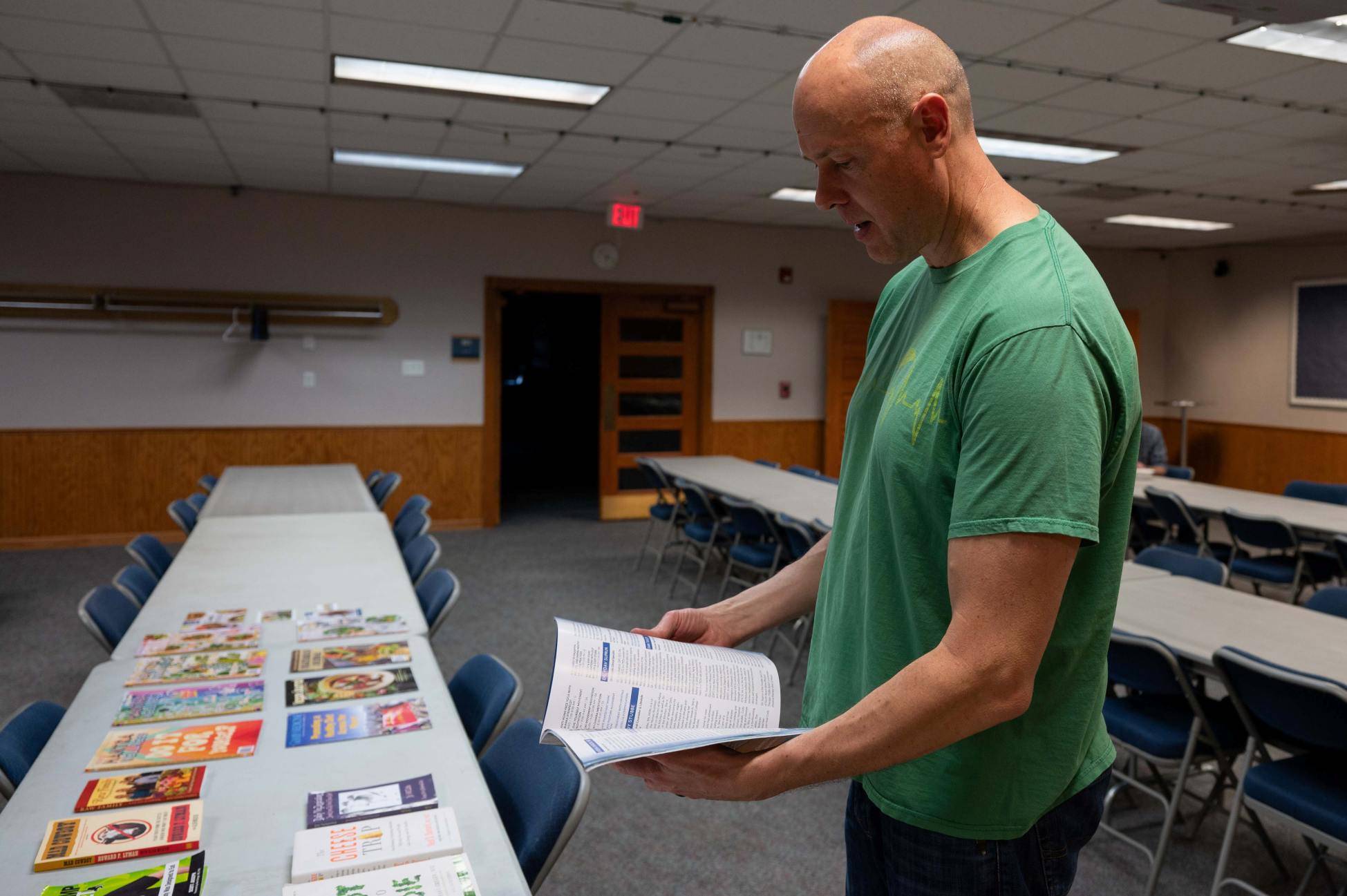

1. Read a Lot

You’ve likely never heard this during your time in the military. Even so, it’s widely known among qualified educators that regular and wide reading is the single most important thing people can do to increase intelligence and mental acuity. These benefits are most obvious when a regular reading habit is established early in childhood, but adults who “aren’t readers” also have a lot to gain by reading more often and more deeply.

Many well-regarded studies show that those who read regularly enjoy many benefits, including but not limited to:

- Up to 20 percent higher raw IQ

- Dramatic gains in deductive reasoning ability, inductive reasoning ability, and problem-solving skills across all categories

- Increased resistance to mental and psychological stressors

- Up to 200 percent increase in writing ability relative to similar-age people who read rarely or not at all (measured in standard deviations)

- 25 to 50 percent decrease in risk of Alzheimer’s, dementia, and similar diseases

- 10 to 15-year delay in cognitive decline related to old age

- Total lifespan increase of 2 to 3 years

2. Train Your Brain with Games and Puzzles

Some games and puzzles, particularly those that train working memory, task focus, and reasoning abilities are strongly shown to produce benefits that transfer directly to other areas of life. If you already enjoy games and puzzles in your down time, you’re already off to a good start, but not all such activities lead to significant mental and cognitive gains. Here are a few for which there is strong evidence:

- Sudoku, which can generate mild to moderate improvements in executive function and working memory

- Crossword puzzles, which help vocabulary, working memory, focus, and general creativity

- Certain video games, particularly those that fall into the broad genre buckets of “strategy” or “puzzle”. These can improve spatial memory as well as problem-solving speed and accuracy

- Chess, which can greatly improve players’ advance planning skills, inductive reasoning, and deductive reasoning if played once or twice per week

3. Continuing Education in Your Military Job

In the military, you’ll receive regular continuing education (usually called “Professional Military Education” or PME), but this is often “bare minimum” material designed primarily to prevent degradation of existing skills and knowledge; mastering new skills for leadership and knowledge are rarely the focus. You can dramatically improve your deployment readiness if you actively take charge of your own PME, and doing so might be easier than you think. Here are some recommended tips:

- Ask for more training: The military is a large, slow-moving bureaucracy, and professional military education (PME) often takes a back seat to immediate demands. Still, you can usually secure approval for additional, high-quality training if you make it easy for your command to say yes. Remember, career progression is ultimately your responsibility. Take the initiative to pursue challenging schools that build mental toughness, leadership, and readiness—such as the U.S. Army Ranger School. Timing may be difficult, but preparation, persistence, and a clear plan will improve your chances. Show how your attendance benefits both you and the unit, and keep pushing.

- Network: You may be surprised how much you can learn from others who were trained in your MOS at different places or times (or who have simply been on the job longer than you have). Even unofficial training or “talking shop” can be hugely beneficial in terms of increasing your ability to do your job well (which also leads to increased confidence and psychological well-being).

- Self-study: Whether you successfully request additional training or not, you can always teach yourself. Reading and watching videos about your military job can be a great way to better yourself in that regard. (Just be careful as things you learn from non-military sources may be considered the “wrong” way or otherwise be unapproved or impractical, but even in those cases, the knowledge is still useful to you.)

Physical Health and Training

As with many of the other topics in this guide, nutrition and fitness are highly individual and heavily context-dependent; few recommendations are truly universal or nearly so. Our suggestions in this section are meant to be broadly useful to most military service members, but your needs may be different. When necessary, work with a doctor, nutritionist, and/or personal trainer to dial in a plan tailored to your body. Also seek help within your unit. You may have a fitness guru who can provide advice on improving. your physical fitness.

Fine-Tuned Diet

Nutrition is a young field in which true scientific certainty is rare and misinformation is rampant. There are only a few broad principles that seem like pretty safe bets for most people in the context of military service, so we’ll limit our recommendations to those.

- Strive for a whole-food diet high in fat and protein: High-quality, nutrient-dense food is not exactly easy to come by in military dining facilities; you may have to do your own shopping and cooking. In general, fresh animal protein and fresh vegetables should comprise the majority of your food intake. (MREs should be a last resort.)

- Avoid sugar and simple carbs: Again, this is a general recommendation with some caveats and situational exceptions, but as a rule of thumb, few foods wreck your body more than sugar and other highly processed, nutrient-empty carbohydrates. Unprocessed sugars like those found in fresh fruit are fine in moderation. Approach carbs with a “use it or lose it” mentality; carb-heavy meals are generally more justifiable (health-wise) if you’re expecting heavy exercise within a few hours after eating.

- Experiment with meal frequency: Many people say “eat one or two meals per day,” and just as many people say “eat four to six small meals per day.” Which is correct? Broadly speaking, neither is correct, because this is highly individual. Try different options with respect to portion size and meal frequency to see what works best for you in terms of satiety and energy levels.

Regular Exercise

Exercise is arguably even more individual and context-dependent than diet. Different military roles and settings call for different kinds of physical fitness; for example, raw strength is more important for combat engineers and heavy weapon operators than it is for scouts and snipers, who really need to be able to walk and run a lot without getting tired.

- Plan your workouts in general terms: This is one of those things that’s easy to overlook because it seems obvious, but military PT generally lacks nuance. Given your military job and other relevant factors, will your next deployment demand excellent cardio, muscle development, a balance of both, or something else entirely (like top-tier swimming skills)? The answer to this question should shape everything else about your workout plan.

- Don’t overdo it: Whether explicitly or implicitly, many military service members have a mindset that there is (almost) no such thing as too much PT. There is absolutely such a thing as too much PT. Over-exercising without allowing your body (and mind) adequate time to rest and recover isn’t merely counterproductive—it’s actively damaging. Figuring out exactly how much and how often you should work out will require tracking and experimentation, because your body’s needs and limitations aren’t exactly the same as anyone else’s.

- Consistency trumps intensity: Military culture promotes the idea that exercise should be intense and brutal. Although punishing workouts have their place, you should not be working out at maximum intensity all the time. In the long run, workouts that are moderate and consistent will always produce better results than those that are grueling but erratic. (Grueling and consistent would violate the “don’t overdo it” rule, so don’t do that, either.) Simply showing up for some kind of manageable exercise every time, consistently over time, is the best thing you can do.

When it comes to PT, the quality of your gear definitely matters. Here are our quick, top five picks for workout clothing.

- Best running shoes: Adidas Men's Supernova Rise 2 Running Shoes These comfortable shoes combine responsive Dreamstrike+ cushioning, supportive transitions, and breathable comfort—ideal for daily training and race prep.

- Best tank top for intense workouts: Adidas Men’s D4T Training Tank Top This moisture-wicking polyester tank is designed for maximum airflow and freedom of movement, helping you stay cool on your toughest training days.

- Best all-around PT shirt: 5.11 Tactical Men’s PT-R Charge Short Sleeve Shirt 2.0 Anyone who runs or lifts a lot knows that not all workout shirts are created equal. This ultra-lightweight shirt keeps you cool and dry without chafing.

- Best hoodie for cold-weather training: Under Armour Men’s UA Rival Fleece Hoodie This warm-but-not-too-warm training hoodie fits snugly at the cuffs and bottom hem while fitting loosely everywhere else, allowing full mobility during any workout.

- Best running shorts: Condor Ranger Panty These lightweight shorts are durable, supportive without being snug, and affordable enough to pick up several pairs without breaking the bank.

Preventive Medicine

This last section of the guide is short and simple, but that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. As the adage goes, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” While you’re on active duty or gearing up for deployment, you have effectively unlimited access to medical care, and you should use it. Be sure to schedule regular physicals, lab work, nutritional consults, dental checkups, and so on. Proactive management of your health very often prevents or at least mitigates health problems that can become chronic or severe if not detected and treated early.